DRAFT

Historical Context

For people in Cambridge, White Creek, Jackson, and Buskirk, Eagle Bridge has long been more than “the place where the tracks cross.” In the second half of the nineteenth century it was a genuine little transportation hub – a spot where two important railroads intersected, where travelers changed trains, and where hotels and boarding houses clustered to feed and house them.

Ken Gottry’s research, combined with old maps and photographs, lets us reconstruct how that railroad landscape worked and where the big hotels – the Dalton House and the Eagle Bridge Hotel – actually stood.

Today the hamlet of Eagle Bridge is usually described as a Rensselaer County place in the Town of Hoosick, but the postal name “Eagle Bridge” also covers much of the Town of White Creek just over the county line.

That blurred boundary helps explain why some nineteenth-century documents describe the Dalton House as being in “White Creek” even though maps label it in Eagle Bridge.

Railroads Come to Eagle Bridge

The “Upper Tracks”: Boston & Maine

The east-west line through Eagle Bridge was part of what later became the Boston & Maine Railroad (B&M). From Troy it ran up the valley through Buskirk, Johnsonville, and Cambridge on its way toward Massachusetts. In local talk this was the “upper track” – slightly higher in elevation and visually above the north-south line.

For Cambridge and White Creek residents, the B&M was the main passenger route to Troy and Albany and, by connection, to Boston and New York. A traveler from Cambridge could ride west to Buskirk or Eagle Bridge, step off at the junction, and connect to a north–south train.

The “Lower Tracks”: Delaware & Hudson

The north-south line was the Delaware & Hudson (D&H), nicknamed the “Bridge Line” because it formed part of a through route from New York State to New England and Canada.

Locally it ran from Albany northward through Mechanicville, Johnsonville, Valley Falls, East Buskirk, and Eagle Bridge, then on toward Hoosick Junction and Rutland, Vermont. This was the “lower track,” both because it sat a bit lower in the valley and because it skirted the river flats more closely.

Residents remember this division clearly. As Gottry recalls, when he asked Buskirk natives about “the upper and lower tracks,” they immediately equated “upper” with the B&M that took them to Hoosick Falls and “lower” with the D&H, used more for freight – coal, animal shipments, and chemicals bound for Valley Falls industries.

A Three-Track World

Old photographs of Eagle Bridge show not just the two mainlines but also a third rail line – an eastbound B&M spur running closest to what is now NYS Route 67. One annotated photo notes that the track in the foreground, once used by the spur, is essentially the location of the modern highway. The Eagle Bridge Hotel sat between that spur and the D&H “lower” tracks, literally sandwiched between rail activity on both sides.

Why Eagle Bridge Needed Hotels

Because the B&M ran east-west and the D&H north-south, Eagle Bridge functioned as a transfer point. Passengers from Troy and Hoosick Falls could change here for trains toward Rutland or toward Cambridge and Salem. Freight cars were also interchanged between the companies at Eagle Bridge’s small yard.

Any such junction needed places where people could:

Wait a few hours between connections

Eat a proper meal

Spend the night if they missed the last train

That demand produced at least two significant hotels within a stone’s throw of each other: Dalton House and the Eagle Bridge Hotel (later remembered locally as Brown’s Hotel).

Dalton House: Early Railroad Hotel on the Edge of Two Towns

Locating the Dalton House

A mid-1860s county atlas map, labels a building on the north side of the east-west railroad as “R.P. Dalton – Dalton House.” It stands just east of the current Eagle Bridge Inn site, between the inn and a small building that later served as an insurance office and, earlier still, as a railroad structure.

Yet an 1866 printed invitation to a “Donation Party and Oyster Supper” describes the event as being held “at the hotel of R.P. Dalton, at White Creek.” On its face that seems to contradict the map.

There are a couple of likely explanations:

Postal vs. municipal address. Many properties technically located in the Town of Hoosick nevertheless had a “White Creek” or “Eagle Bridge” postal address. The modern ZIP code 12057 still covers both Hoosick and much of White Creek.

Community identity. Residents might have thought of the entire junction village – on both sides of the county line – as part of the broader White Creek community, especially in church and social contexts. The benefit for Rev. H. J. Lewis, named in the invitation, may have involved a White Creek congregation, prompting the “at White Creek” wording.

So the map and the invitation can both be correct: Dalton House physically stood in Hoosick/Eagle Bridge, but was part of the White Creek social world.

The Dalton Family and Their Hotel

R. P. Dalton (likely Robert P. Dalton, though this would need confirmation from census and deed records) operated his hotel when the railroads were still relatively new. The building in the real-photo postcard labeled “The Old Dalton House – Eagle Bridge, N.Y.” shows a three-story, front-gabled structure wrapped with generous two-story porches – classic railroad-era architecture designed to impress travelers arriving by train or carriage.

Given its position, Dalton House would have attracted:

Railroad workers lodging near the yard and depots

Commercial travelers selling goods up and down the valley

Local residents coming in for meetings, dances, and the sort of donation party advertised in 1866

Its porch railings and multiple side entrances in the photograph hint at a lively social space rather than a simple roadside tavern.

The Dalton House later disappeared – likely torn down in the early automobile age – and the site became a parking lot alongside the Eagle Bridge Inn, as remembered by Ken Gottry and others. That loss makes the surviving photographs especially valuable.

Eagle Bridge Hotel (Brown’s Hotel): The Grand Junction Inn

A Hotel Between the Tracks

If Dalton House was impressive, the Eagle Bridge Hotel was massive. Photographs show a broad, three-story structure with a full two-story porch facing toward the tracks, built about 1853 according to local tradition. One annotated aerial photo, probably from the early twentieth century, clearly places the hotel between the upper B&M alignment and the lower D&H line, only steps from the joint station.

The hotel served as a joint railroad station for both D&H and B&M trains. Passengers could step off a train, cross a platform, and walk directly into the hotel or onto its porches while they waited. Later views show a small signal tower and the tangle of tracks and platforms that surrounded the building.

Ownership changed hands several times – E. C. Reynolds in the 1850s, G. B. Fitch in the 1880s – a sign that the property was substantial enough to attract investors. Local people later referred to the site as Brown’s Hotel, reflecting a later proprietor whose name stuck in community memory.

Fire of 1916

In 1916 the Eagle Bridge Hotel burned, taking with it the dominant landmark of the junction. Newspaper coverage from that time (which could be followed up in Troy or Hoosick Falls papers) would likely describe the fire and note any injuries, but even without the details we know that:

The hotel was never rebuilt on the same scale.

-

The property was eventually reused; by 2021 the Eagle Bridge Post Office occupied the site.

The combination of fire, the rise of the automobile, and the gradual decline of long-distance passenger rail after World War I doomed many such railroad hotels across upstate New York.

The Railroad Yard: Depots, Creamery, and Everyday Life

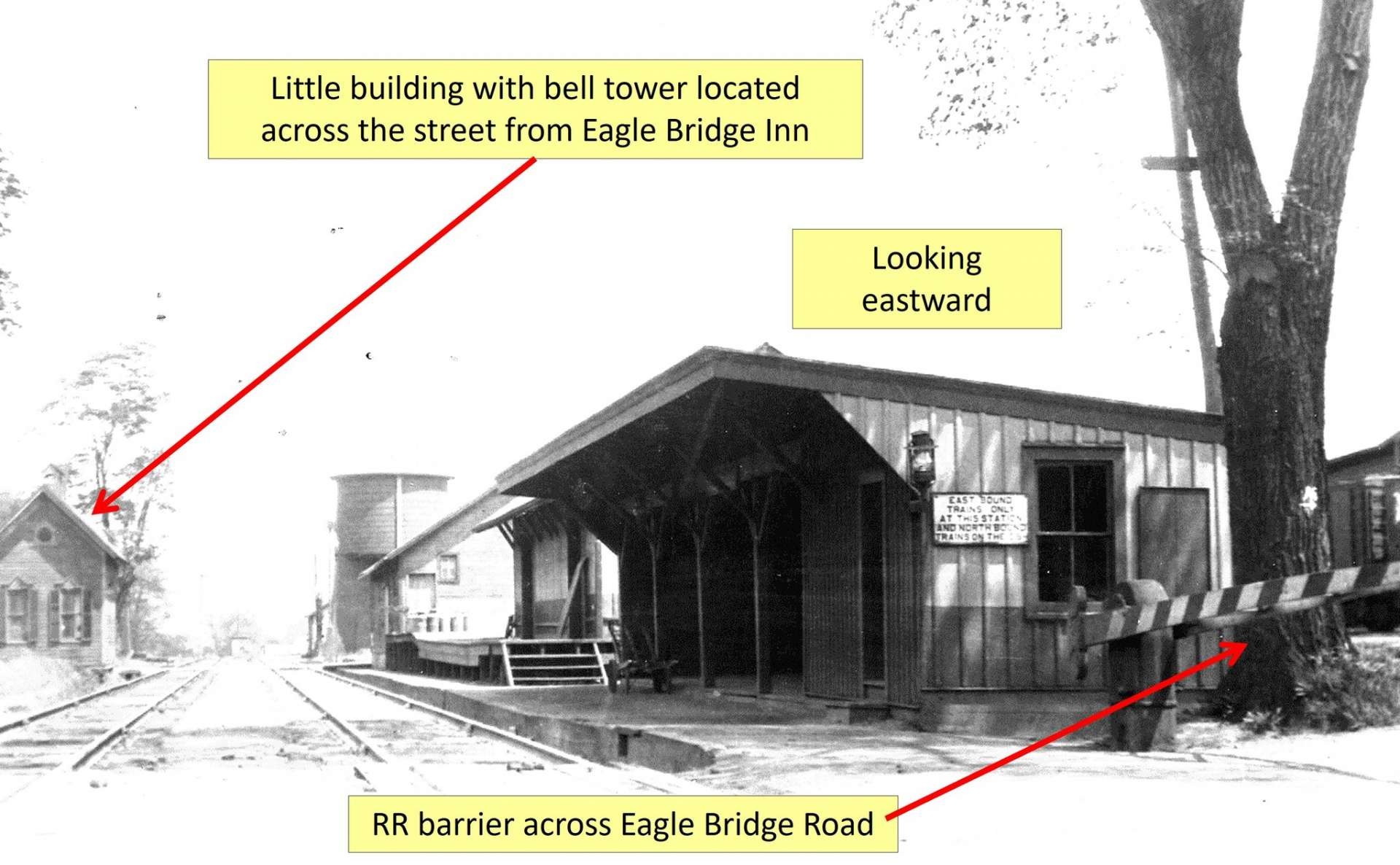

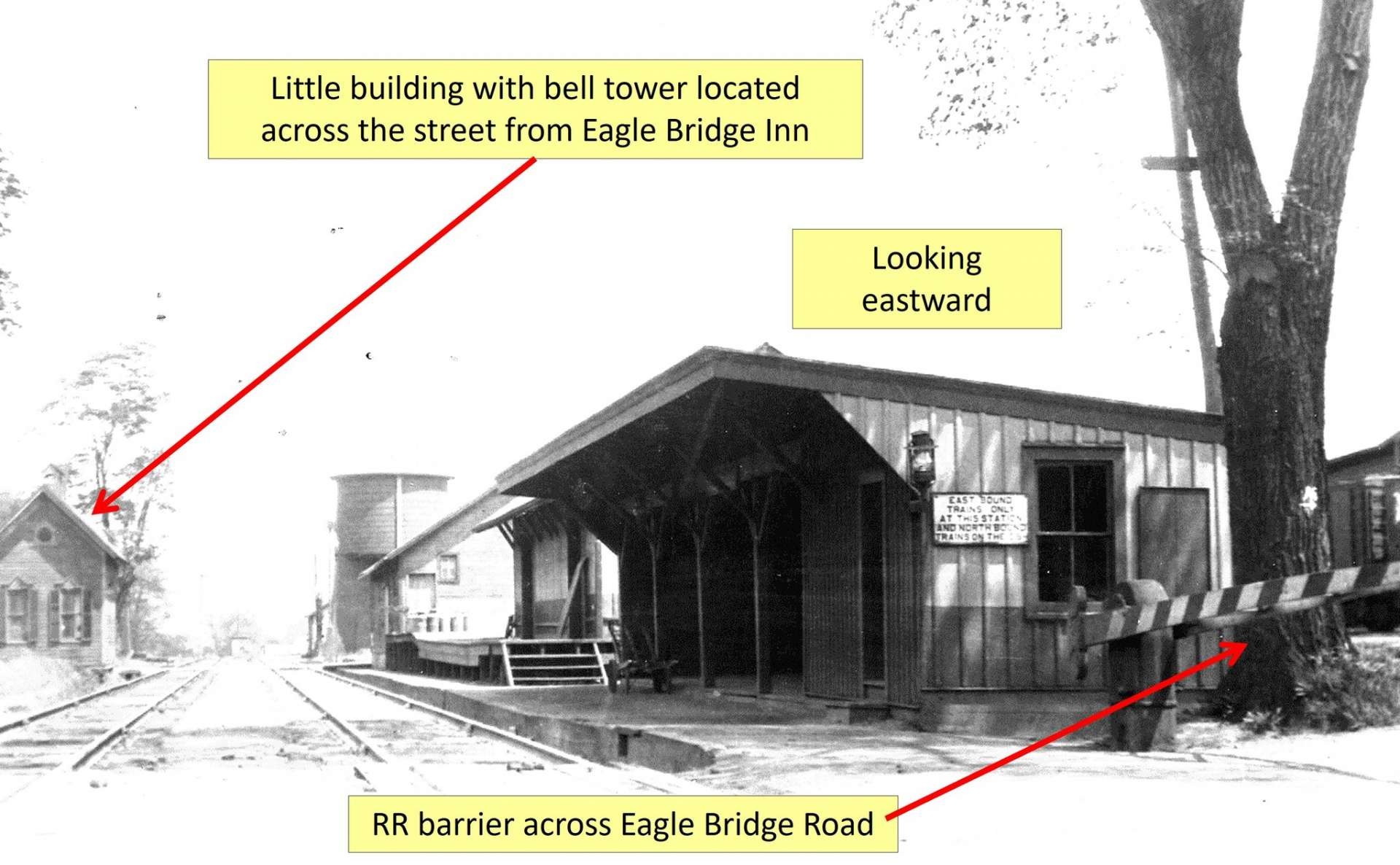

Gottry’s image set also includes several scenes of the rail yard south of the Eagle Bridge hotels, across what is now NY 67:

A long, low freight depot building with wide loading platforms.

A water tower and small trackside structures.

A creamery – later used by the Batten Kill Railroad era as a key milk-shipping point.

Eagle Bridge became famous for being the location of the last bulk milk shipment by rail in the United States, a load of milk sent from Eagle Bridge to Boston in August 1972.

That event capped nearly a century of dairy traffic from Washington County farms through Eagle Bridge’s creamery and onto the B&M.

The yard also handled coal for heating, livestock, and – as one local recollection notes – tank cars hauling chemicals to the big cordage factory in Valley Falls along the D&H.

Everyday life around the junction was noisy and busy:

Crossing gates and barriers like the one visible in the early depot photo controlled wagon and later automobile traffic over the main street.

A small, bell-equipped building across from the Eagle Bridge Inn probably served either as a railroad office, signal tower, or community building.

Children in Buskirk and surrounding hamlets walked or rode to the “upper track” to catch the B&M for school in Hoosick Falls, while freight men paced the “lower track” as track walkers.

Connections to Cambridge, White Creek, and Buskirk

For Cambridge-area residents, Eagle Bridge was both gateway and neighbor.

Cambridge Station, on the same B&M line, lay only a few miles west. Passengers from New York City or Boston often changed at Troy onto a B&M train, rode through Johnsonville and Buskirk to Eagle Bridge, and continued on to Cambridge, Shushan, and Salem.

Farmers from White Creek and Jackson hauled milk and cream east to the Eagle Bridge creamery, especially after small local creameries consolidated.

The overlapping identity of Eagle Bridge and White Creek – visible in that 1866 Dalton House invitation – reminds us that church, school, and shopping networks didn’t stop at county lines. Residents moved easily between Rensselaer and Washington Counties, and the railroad junction made that even easier.

Buskirk shared the same “upper” and “lower” track relationship, but without the same concentration of hotels. In effect, Eagle Bridge was the bigger, more intensely developed rail village that served the whole corridor.

Decline of Passenger Service and the End of the Hotels

By the mid-twentieth century several forces reshaped Eagle Bridge:

Automobiles and improved highways allowed travelers from Cambridge or Hoosick Falls to drive directly to Troy, Albany, or Bennington, bypassing the need to change trains at Eagle Bridge.

Passenger rail service shrank; the Rutland no longer carried crowds to Vermont resorts, and the B&M cut back schedules.

The 1916 fire had already removed the largest hotel; Dalton House and other smaller lodging houses gradually closed or were repurposed.

Freight traffic lingered much longer – especially dairy – but by the 1970s even that was fading. The Batten Kill Railroad saved some of the old D&H trackage to serve remaining industries, but the era of Eagle Bridge as a bustling passenger junction was over.

Today, to drive through Eagle Bridge is, as one Facebook commenter put it, “a sad state of affairs” – at least compared with the photographic record of packed porches, busy platforms, and semaphore towers. Yet the surviving depot building, the alignments of the tracks, and the open spaces where Dalton House and the Eagle Bridge Hotel once stood still tell the story to anyone who knows what to look for.

Legacy and Present-Day Significance

For the Village of Cambridge and surrounding towns, the story of Eagle Bridge’s railroads and hotels is part of a broader regional history:

It explains why Cambridge developed with such strong connections to Troy, Albany, and Hoosick Falls – the rail lines that linked them ran right through Eagle Bridge.

It highlights how hamlets like Buskirk and White Creek fit into a shared transportation web, even when county boundaries and modern postal designations make them look separate on today’s maps.

It reminds us how much of local social life – from donation parties for ministers to commercial travel and seasonal farm labor – once revolved around railroad timetables.

For public historians and local researchers, Eagle Bridge also offers a rich case study in landscape change: how hotels rose and fell with the railroads, how highways reused rail alignments, and how small service buildings were dragged, repurposed, and reinterpreted over time (as with the former railroad building turned barber shop and insurance office beside the Eagle Bridge Inn).

References & Further Reading (Suggested)

Because much of this story comes from maps, photographs, and community memory rather than a single printed history, further documentation will depend on digging in local archives. Useful leads include:

Beers’ Atlases of Rensselaer and Washington Counties (1860s–1870s) – for property ownership and the location of Dalton House and Eagle Bridge Hotel.

Town of Hoosick and Town of White Creek assessment rolls and deed books – to trace ownership of the Dalton and Brown/Hotel parcels.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century newspapers from Troy, Hoosick Falls, and Cambridge (obtainable via the New York State Historic Newspapers site) – for advertisements, fire reports, and railroad timetables.

Railroad histories and timetables of the Boston & Maine and Delaware & Hudson, including resources compiled by the Nashua City Station historical group and railfan publications.

Grandma Moses-related collections at the Bennington Museum and other repositories, which sometimes feature her paintings of Eagle Bridge Hotel and the junction landscape.

Washington County and Rensselaer County historical societies and local historians, who can often provide copies of photographs like those Ken Gottry has shared and may have oral histories from residents who remember Brown’s Hotel, the Eagle Bridge Inn, and the last years of passenger service.

Add Row

Add Row  Add Element

Add Element

Write A Comment